(This is

the second in a series of posts on rare studio tracks by TSOM from the

1980-1985 period, following on from an earlier post on Driver)

In the twenty years that followed the

release of First and Last and Always and the accompanying No Time To Cry single

in March 1985, only the efforts of a series of intrepid bootleggers and

tenacious collectors enabled any alternative or previously unreleased studio

recordings from that era to surface, and by the turn of the millennium it was widely assumed

that the vaults were empty and that there was nothing left to emerge. Whilst

the original FALAA album had been repackaged and re-released on several

occasions since its original launch, there was consternation amongst Sisters

aficionados when it was announced in 2006 that Rhino (a division of WEA) was to

re-release the three studio albums … with additional tracks. Not only did this

mean that some songs were to be available digitally for the first time, but

incredibly two previously unavailable tracks were to be included, an eleven

minute version of “Neverland” on “Floodland” (unlike the brief “fragment”

available on the original LP) and an “Early” version of “Some Kind of Stranger” on FALAA (click the link to hear it on YouTube). It was hoped that this might perhaps include an extra opening verse,

as the released version started with the word “And (yes I believe

in what we had)”, implying a continuation of a previous train of thought.

Nothing, however, could have prepared said fans for the reality of what they

were about to hear for the first time.

“Some Kind of Stranger” had by this

stage become recognised as a key song of the Eldritch/ Marx/ Hussey/ Adams era, the centre-piece

and dramatic climax of the venerated FALAA album. Every classic LP seemed to end with an

epic song which elevated what was already an incredible album to legendary

status – “The End”, “I Am The Resurrection” and “Champagne Supernova” being but

three examples – and in the Eldritch/Marx composition “Some Kind of Stranger”,

the Sisters showed that they could marry their new found pop sensibility (as on

“Walk Away” or “Black Planet”) with the ability to construct a slow-burning

symphony of a song, following in the tradition of “The Reptile House” EP. Save for SKOS and “(Amphetamine) Logic” which preceded it on the album running list,

far more original fans of the band from the Gunn era would have deserted the

band than had already done so. Disappointinglyhowever, the song was only played “live”

on a handful of occasions (initially on the “Black October” UK jaunt which had

been planned with the album release in mind, with the first playing at Birmingham's Powerhouse having been kindly uploaded to YouTube by Phil Verne, head honcho of the wondrous unofficial The Sisters of Mercy 1980-1985 Facebook group) , reflecting the physical and

emotional demands of the song on the band and particularly singer as well as

the difficulty in reproducing the multi-layered build-up with just (a maximum

of) four men and an Oberheim drum machine. (Part of SKOS would return to the

live set in the 1990s as a medley with the band’s cover version of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb”.)

The original album version of SKOS

could hardly be more bombastic, starting with a somewhat pretentious and

vaguely ominous crescendo of echoing sound unlike anything else the band have

recorded, ambient and harmonic. After a couple of seconds of dramatic silence, Marx’s

complex riff kicks in, playing solo for a couple of bars before the other

band members join the fray. Barely twenty seconds into the de facto start of

the song, and a couple of bars earlier than might have been expected,

Eldritch’s booming baritone intones the opening line, "And yes I believe in what we had". Marx’s riff is

certainly a step beyond those produced in the early days, and he alluded

to this in comments to Robert Cowlin for his excellent blog article on FALAA :

“Any fans from the pre-Warner’s era would doubtless say that, for all its

strengths, there isn’t a guitar line to match Alice anywhere on those finished

tunes.” The guitarist had certainly moved away from the one-dimensional single

string riffing which had become famous for and which he himself mocked with

typical self-deprecation on the Ghost Dance website: “’All on one string and

job’s a good ‘un’ as Choque from Salvation was keen to point out….the riff

steps up half-way through the verse on the early Sisters stuff…Alice,

Floorshow, Good Things…kind of a nod to bands like The Cramps who we all

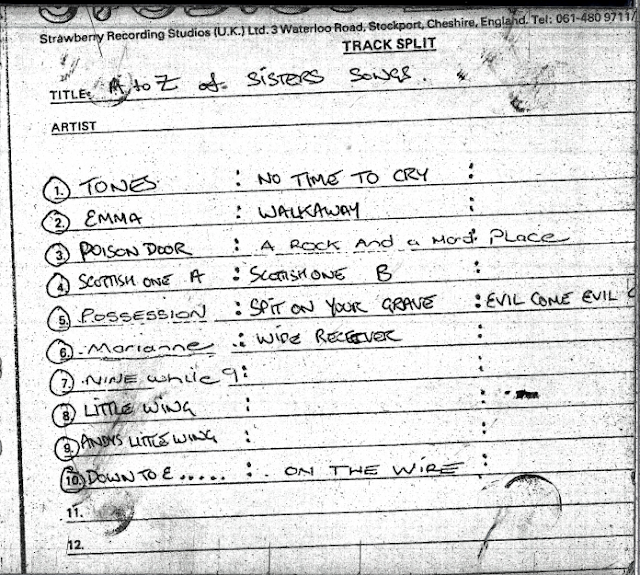

loved.” Indeed, on the studio reels from the Strawberry Studios session, the then

untitled Some Kind of Stranger is referred to as “Little Wing”, presumably

because of its fleeting similarity in terms of rhythm and melody to the legendary Jimi Hendrix’s riff on the song of the same name, a comparison Marx

could not have dreamt of a couple of years earlier.

The album version of SKOS had boasted a

lengthy introductory section in which a self-justifying Eldritch seems to be

explaining why a long-term relationship has come to an end despite all of his

own best efforts, and how a communication breakdown had been a key factor

(“words got in the way”, “Lord knows I tried to say”, “heard a million

conversations going where they’ve been before”, “all of my words are

second hand and useless” etc), suggesting the narrator’s belief that language

is an ultimately unsatisfactory medium for communicating deep human emotions.

He then goes on to excuse presumed infidelities (“the world is cruel, and

promises are broken”) by expressing the view that wordless (“don’t give me whys

and wherefores” “I don’t care for words that don’t belong”) passion with a

stranger is somehow more intense, true and important than working through the

ups and downs of a long-term relationship. Whilst his view “And I don’t care

what you’re called, tell me later if at all” may seem callous, it is clearly an

honestly held view, as he implores the “beautiful” “angel” with the “unknown

footsteps in the hall outside” to “come inside” through his “door open wide”.

Hardly a novel approach for a rock lyricist (everything from Extreme’s “More

Than Words” to, erm, Right Said Fred’s “Don’t Talk, Just Kiss” express the same

sentiments albeit in less poetic form), and the theme of a rock star seeking

satisfaction in meaningless sex with nameless groupies is as much a rock’n’roll

cliché as shades and dry ice.

However, the lyric had added personal

poignancy for Eldritch who (according to Gary Marx interviewed in 2003 by

“Quiffboy” for Heartland Forum) at that time “was effectively splitting with

his long-term girlfriend and I was leaving the band. The two things led to a

number of references in the lyrics which seemed to cover his farewells to us

both. ‘Walk Away’ may or may not be about me, I don’t care because I don’t

particularly like the song.” Unlike SKOS, Marx was of course not responsible

for the melody and therefore felt no sense of betrayal for ‘Walk Away’. The

same could not be said for SKOS: “The one lyric which always bugs me is the

line from SKOS which says, ‘Careful lingers undecided at the door’, which I

definitely took as a shot at me.”

Marx had already light-heartedly complained about

Eldritch’s lyrical take on SKOS in a March 1985 interview for Artificial Life fanzine. “I would think that SKOS is the best attempt to sort of come out

totally the opposite of what it was when I started it. It’s Andy’s big ‘woman

song’…it’s his ‘I want every woman in the world’ song and I wrote it [the

melody] totally from the opposite standpoint. When I wrote the music it was my

version of the ‘Wedding March’. It was like a real, lasting relationship song…very

strong, too! It works well because it’s quite emotional and to me it’s sort of

tucked between the two because it’s like one person saying ‘I want every woman

in the world’ and the other saying ‘Ah but when it all boils down to it, when

you’re on your death bed, there’s only one that you’ll want to see’…and that

makes it really emotional. It might not to other people because they might

think, ‘I want every woman in the world as well!’”

In another interview from that month

published in Sounds, Eldritch explains his own vision of the song. “The thing

is, with a band like us, people figure that they know us inside out already.

All the basic emotions and stuff are very public. And so casual sex isn’t

really that casual. It just bypasses all that ‘Shall-I-take-you-to-the-pictures-for-five-weeks-before-we-start-feeling-up-each-other’s-jumpers.’

With SKOS, the visual picture was very hot and humid, sort of one door closes,

another door opens. But the way it turned out – unfortunately, I’ve got the

sort of voice that sounds desperate, and the higher it gets, the more desperate

it sounds. It just sounds like a dirge to me.” The tales of an exhausted

Eldritch having to be forced up to the studio microphone to provide a

distressed vocal for a long-finalised backing track ring true no more so than

on the album version of SKOS, but all of what has been discussed so far pales

in significance when compared to the Early version that was finally released on

the 2006 Rhino CD edition…

The Early version is still

recognisably the same song both sonically and lyrically, but with enough

significant changes to make it a very different experience for the listener.

The Early version, listed as “Andy’s Little Wing” on the studio reels,

dispenses with the ambient soundscape before the song begins, beginning instead

with a particularly echoing drum beat. The second surprise is that that the

vocals miss their usual cue…by several minutes. Instead the listener is able to

focus on the subtleties of Marx’s composition, with Adams’ bass to the fore,

and keyboard adornments prevalent from relatively early on. At 1:41, the first

keyboard flourish is heard as the song builds in complexity in the style of

Kiss The Carpet, making one wonder whether this song was considered as a

potential set opener for the FALAA era. The main keyboard riff that features

towards the end of the album version makes it first appearance in the intro

here, around 2.15, over some rather rough-around–the-edges guitar chords that

would probably have been rounded off in any final version for contemporary

release.

After such a lengthy instrumental

introduction, it comes as almost a surprise when Eldritch eventually starts

singing at 3.40. Even more surprising are the opening lyrics themselves, which

give a completely different slant to the song. Whereas the album version can be

read either as a farewell to Marx and an appeal to a glamorous (LA based?) “angel” to

join Eldritch’s next project, or as a farewell to his long-time love and as an

explanation for his on-tour dalliances, the Early version paints a different

lyrical picture.

“From England in the morning

I haven’t slept for days

I haven’t kept the promise made”

The opening line (“From England in

the morning”) suggests that the narrator has just arrived in a foreign country

after an overnight flight or ferry, and is addressing a female acquaintance in

the overseas territory, whilst the following line (“I haven’t slept for days”)

seeks to either impress or elicit pity. Whether the insomnia is caused by

travel, amphetamines, studio recording sessions or romantic shenanigans is not

elucidated. The third line to not make the final cut of the song, “I haven’t

kept the promise made” seems the most portentous, the vocal line descending

over a minor cadence in the style of an ominous line in a stage musical, or the

final line of the slow section in Brel’s “Ne Me Quitte Pas” (better known to

Marc Almond fans as “If You Go Away”). As with most Eldritch lyrics, again this

line is open to various interpretations. To whom had a promise been made?

Himself? His former partner in England? The overseas friend? And what was the

promise? To dump his former love definitively? To remain faithful? To keep off

the drugs and take better care of himself? Whatever the explanation, there is a clear admission of guilt in this phrase, a stark contrast to the self-justification evident in the final album version lyric. The song then goes straight into the

middle section of lyrics from the album version, “And I know the world is cold

but if you hold on tight to what you find etc”, addressed to the “stranger”,

meaning that there is none of the “And yes I believe in what we had, but words

got in the way etc” addressed to the former friend. The Early version is

therefore entirely aimed at “some kind of stranger”, and is lyrically less

dense as a result.

If Eldritch was worried about how

desperate his upper range sounded on the finished album version of the song,

one can understand why the Early version was kept well-hidden for twenty years,

as the “And I don’t care what you’re called” section which heralds the jump in

octave reveals a wild, raw and emotionally bare tone previously unheard from

the singer. Robert Cowlin’s definitive guide to the FALAA recording sessions

points out the vocal take is very much in the style of the guide vocals

provided on other demo versions from the sessions, and certainly Eldritch’s

vocal here is well below the polished, professional standard of the final FALAA

mixes, but all the more emotive for that.

Equally disconcerting for the

listener is a bizarre guitar solo which commences at around 4:35. A muffled

jazz-blues solo totally unrelated to anything else heard on a TSOM record, the

early comments in 2006 by the denizens of Heartland Forum were not kind,

likening the somewhat intrusive (particularly when heard through headphones) sound

to “someone sitting on a puppy”, and the solo wails along faintly in the

background for the remainder of the song in free-form style. This four-minute

climax is entirely filled with Eldritch seemingly extemporising on the “I think

you’re beautiful, angel/some kind of stranger come inside” theme, like he did

with the early live versions of “Walk Away” or on the “No Time To Cry” Peel

session before the lyrics for those songs were finalised. Sounding ever more impassioned,

Eldritch’s grip on the melody, which might be charitably described as “pitchy”

throughout, becomes almost painfully out of tune just before the seven and then

eight minute marks, and then once more in the final phrase at 8:30. The song

then fades rapidly over a guitar outro, meaning that a full version would have

weighed in at over the nine minutes mark, two and a half minutes longer than

the final album version (not including the soundscape intro).

As well as giving another insight into the TSOM songwriting process, Some Kind of Stranger (Early) is a stunning song in its own right which is some way best reflects the on-edge atmosphere within the band during the second half of 1984.

My thanks for this post are due to Robert Cowlin, Phil Verne, and others who have contributed either knowingly or unwittingly.

No comments:

Post a Comment