Labelling or pigeonholing of artists into specific genres and the development of youth cults along these tribal lines was very well-established by the time The Sisters of Mercy emerged in the early 1980’s. As mentioned in the band’s own online biography and examined in much greater detail in Mark Andrews’ seminal Paint My Name in Black and Gold biography, The Sisters developed very organically out of the Leeds punk and post-punk scene of the late 1970’s, which was very loosely centred around gigs promoted by John Keenan under the F Club banner.

Whilst The Sisters remained true to the quintessential

tenets of the early punk movement, with the DIY ethic extending beyond the

usual rudimentary inability to effectively master instruments (a charge however which

Gary Marx readily admits to) into the more political elements such as founding

their own record label rather than (as most of the original punk icons ironically

had) signing deals with major record labels and effectively working for “the

man”, the music scene had fragmented considerably with a number of competing

musical movements fighting for dominance.

The Futurist trend, with its more synth-based sound and

(Bowie-obsessed) androgynous looks was spreading out from its Blitz club base

in London into the UK provinces at the turn of the decade, with Soft Cell the

most prominent exponents in Leeds, whilst the New Wave of British Heavy Metal

(dominant in the West Midlands and North-East of England), moving back to

simpler song structures (influenced by punk) as expounded by Black Sabbath and

Motörhead

also emerged in the very late 1970’s.

Add to this the Mod revival (especially in the broader

South-East region), with fans of The Jam also following the many groups (Purple

Hearts, The Chords, Squire etc) inspired by sharp-suited 1960’s Britpop as

exemplified by The who and The Kinks, and the multi-ethnic Two-Tone ska revival

(again in the West Midlands as well as London – Madness, the Specials etc), and

the UK charts were awash with an eclectic mix of styles and influences, with

British reggae acts (Aswad, Black Uhuru and, erm, Musical Youth), American rockabilly

revival (Matchbox, The Stray Cats) and

Travolta-inspired disco acts all enjoying increased popularity.

The ever-changing musical landscape was summed up by the lyrics

to old skool punk band Vice Squad’s 1981 track (Another) Summer Fashion,

bemoaning the fickleness of youth as their own favoured genre, punk, became

increasingly distant from the mainstream. (“1977, be a punk, 1978 be a mod,

1979, be a skin, 1980 another summer fashion…”).

The complex and seemingly fragmented and compartmentalised

musical scene confused the music industry, with shorter-lived trends making

investment in individual acts and scenes more risky, with bands able to

seamlessly shift from being considered avant-garde cutting edge acts to

mainstream megastars almost overnight (eg Adam and the Ants, The Human League)

in a way that would seem impossible today.

The reality was that many teenagers were happy to dip in and

out of different scenes, with the emerging Futurist/Alternative nightclubs

finding that their punters wanted not just synthpop, but also the harder-edged

sounds of post-punk, and most music fans were happy to profess affection for

bands of different genres beyond tribal lines.

Andrew Eldritch himself, or rather Andrew Taylor, is an

excellent example of this. A Motörhead/Hawkwind fan whose favourite

record in his final year at school (according to an old schoolmate on the

website Friends Reunited a few years ago) was apparently Rainbow’s Rainbow

Rising, by the time he began his undergraduate degree at St John’s College,

Oxford, he was a Bowie obsessive in the words of a fellow student. By the late

1980’s, with Leeds dominated by the agit-prop post-punk of Gang of Four, Mekons

and Delta 5, Eldritch had naturally gravitated to this movement, following the

musical zeitgeist, with his appearance also evolving along the lines of punk

icon Joey Ramone.

With the benefit of hindsight, The Sisters of Mercy have not

only been categorised as Goths (a label Eldritch has always fervently

rejected), but often lauded as the de facto leaders or quintessential act of

the genre. But in their early years, certainly pre-1984, a combination of

factors (the band’s insistence on staying in the North) and the difficulty in

squeezing them into any musical pigeonhole (with the band publicly distancing

themselves from the Batcave posi-punks) can be seen as a significant factor in

the music industry’s inability to recognise a major new talent despite rave

live reviews, rapidly increasing sales and an ever-growing number of t-shirts

and leather jackets sporting the famous head-and-star logo amongst the nation’s

youth.

That The Sisters of Mercy were shunned by the punk scene

from which they developed might be considered surprising, given that they clung

to the DIY ethic longer than the vast majority of bands (Crass being a notable

exception), but by the time the Sisters released their first record in December

1980, punk had itself fragmented. Whilst many of the original more

opportunistic art school or ex r’n’b pub rock punk bands were still recording

and making the charts at that time, they had moved away from the three powerchord

blueprint to explore other genres (The Clash’s street reggae obsession being a

prime example), leaving a gap exploited (pun intended) by working-class

provincial acts who were almost a bleaker, no-nonsense, uncomplicated

caricature of the original “can’t play” “no future” mantra, such as the bands

on Bristol’s Riot City label (such as Vice Squad), Stoke’s Clay Records (GBH,

Discharge), Nottinghamshire’s Rondelet Records (Anti-Pasti), and the main label

likes of Angelic Upstarts, UK Subs and Cockney Rejects, not to mention the capital’s

whole skinhead Oi movement with its (to my view as an outsider) strong British nationalist (i.e.

racist) undercurrent. As the studded leather jacket and mohawk look became a

more prominent punk uniform in shopping centres up and down the UK at this

time, the music itself had also become less creative and more cartoonishly formulaic,

meaning that the original shock and outrage had long since lost its lustre. (Incidentally,

this would be mirrored in the late 1980’s with the second generation of “goth”

bands gleefully adopting the epithet which the original artists shun to this

day, and willingly draping themselves in the most obvious lyrical and visual

tropes of the genre).

Derided “hippy” affectations and concepts which the Year

Zero mentality of 1977 had seemingly blown away made a steady return for those

prepared to move away from the “destroy” caricature of punk, with original

punks Siouxsie and the Banshees, John Lydon’s P.I.L and Howard Devoto

(ex-Buzzcocks, now Magazine) using more sophisticated time signatures and chord

progressions to maintain the original excitement and novelty which punk had

aroused in its listeners, earning the label “post-punk” at the time.

A further group of bands had independently taken these baby

steps away from hardcore punk sounds and developed ideas further, such as

Killing Joke, Bauhaus, Theatre of Hate and UK Decay, whose records and gigs

would appeal to many of those who had originally been fans of bands from the

darker side of punk, such as The Stranglers and The Damned.

On the other flank, The Exploited’s spring 1981 release Punk’s

Not Dead was seen as a clarion call of defiance to those still clinging to

the original punk ethic, but to more causal observers it appeared as a more

desperate exercise in self-delusion, a counter-intuitive admission that the

genre was in fact by now a busted flush.

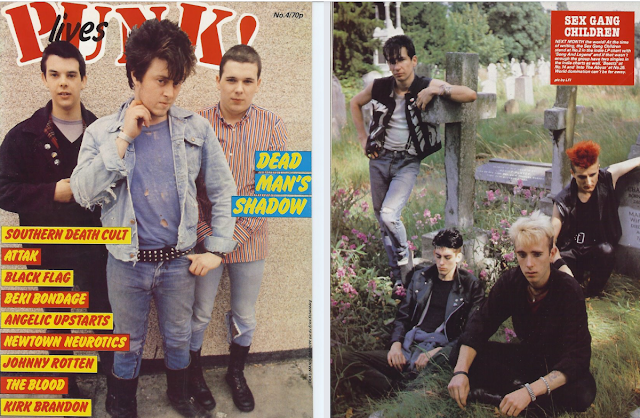

Nevertheless, the phrase certainly galvanised elements of the music industry into believing that punk was a cash cow from which further filthy lucre could effectively be milked, the various Pistols releases from Sid Sings to The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle being high-profile examples of this phenomenon, and one further very tangible example of this was the launch of the glossy Punk Lives! magazine, which ran for eleven issues between 1981 and 1983, launched by the same publisher (the exclamation mark as well as the magazine format is the giveaway!) who was by then already enjoying success with the zeitgeist-riding metal-obsessed Kerrang!

The existence of this wonderful complete online archive of

all eleven issues of Punk Lives!, combined with the known fact that The

Sisters of Mercy were themselves at their artistic peak in the “golden years”

of 1981-1983, allows us a retrospective insight into the complex scene at that

time, and hints at reasons why the Leeds band’s rise to the top was slower than

should have been the case.

Like Kerrang!, Punk Lives! was a tried and

trusted mix of bedroom wall-friendly full page posters, band interviews, record

and live reviews, and a lively letters page which makes for fascinating reading

over four decades later.

Those familiar with the perennial tiresome “gatekeeping”

debate amongst fans of what is currently described as “goth” on the

contemporary scene (which in a nutshell means that fans of guitar-based “trad

goth” deride darkwave Depeche Mode-inspired acts as “synth pop”, whereas fans

of the latter would consign Sisters-influenced acts to the “heavy metal”

category) will be saddened to learn that this mentality seems to be inherent in

the inveterate music obsessive, as Punk Lives!’s readership let the

editorial team know in no uncertain terms whether they should be focussing on

more creative, “positive punk” artists like Southern Death Cult or Sex Gang

Children, or whether these make-up wearing clothes horses should instead be

banished from the magazine’s pages.

The front covers of each issue certainly give some indication of the very broad spectrum of bands contained within – would fans of The Danse Society be interested in Resistance ’77? – and this growing rift as the newer bands began to prosper was probably a reason for the magazine’s eventual folding, hastened by the positive punk lurch of (“new”) ZigZag magazine in autumn 1983. The divide is best summed up in issue 4 of Punk Lives! by guest journalist Al A of fanzine Kill Your Pet Puppy, who traces the dichotomy back to “1980: What was there? The Psychedelic Furs, The Cramps, Bauhaus: music without morals. Crass: morals without music.” A square the Punk Lives! journalist team vainly continued to attempt to circle, a financial necessity apparent after the lengthy absence between issues 2 and 3 with a (coincidental?) lurch away from traditional punk towards greater inclusion of what would retrospectively be termed “goth” bands.

Astonishingly, looking back through the editions, even

though most of the proto-goth bands get frequent mentions in Punk Lives! as

the editor attempted to ride several horses at once, The Sisters of Mercy merit

only one mention throughout the eleven issues, a brief and not particularly

informative review of the Anaconda single in the spring of 1983.

The Sisters should have been ideal fodder for the magazine, with a singer (still pre-hat) who would appeal visually to old Ramones fans, and an incendiary live show that was blowing established punk bands off-stage at gigs. Other bands of similar standing at the time – who, one might cynically add, would have

enjoyed the plugging of bigger record labels - fare significantly better. Alien

Sex Fiend for example feature in five issues of Punk Lives! with live reviews, an interview

and a poster as well as two cover mentions. Xmal Deutschland also feature in

five issues and get the poster treatment, whilst Sex Gang Children, Theatre of

Hate/Spear of Destiny, (Southern) Death Cult, Flesh for Lulu and even Skeletal

Family feature significantly more prominently than TSOM, who had of course been

cover stars of Sounds already by December 1982.

Ultimately, the real reason for The Sisters’ lack of column

inches is revealed during the Punk Lives! interview with New Model Army,

with Justin (still known by the DHSS-confusing nickname of Slade the Leveller

in those days) in particular explaining very coherently the essential laziness

of London-based journalists and labels who thought that talent would naturally

beat a path to their door, an attitude deeply entrenched in the much-loathed

(in the North, at least) editor of the first issue of Punk Lives!, the

Oi-championing London-centric Garry Bushell. The NMA interviewer, “Old

Shatterhead”, sadly dismisses the whole North v South issue as “pretty much old

hat, one of those interview subjects which tends to arise now and again.” But

instead of perhaps contemplating why that might be the case, Justin’s patient

explanation that “it does create a bit of bad feeling” and the irony of the

interview with the Bradford band taking place in a London pub is seemingly

lost.

With gig reviews being based on shows in the capital or,

somewhat randomly, at the Gala in Norwich (one of the journos visiting his

parents on expenses?), Punk Lives! was destined to appeal mainly to

London-based readers or those wanting to wallow in 1977 nostalgia, as provincial

UK82 streetpunk scenes were also largely ignored as the magazine failed to move

with the times.

The same charges of being both out-of-touch and somewhat obviously desperately searching for an audience (presumably no coincidence...) can also be levied at some of the other glossy music mags at the time. Although ZigZag magazine had always been always been a broad church, some of the issues by the early 80's would have struggled to find a regular readership amongst audiences who were increasingly identifying with sub-tribes. It's hard to imagine fans of Wham! being keen on reading about the Virgin Prunes, or Belle Stars aficionados being keen to find out more about UK Dekay (sic) in the July 82 issue, and the similarly eclectic mix of November that year (Dollar and the Damned? Bauhaus and Shalamar anyone?) continued a decline which continued until the magazine went "full goth" under Mick Mercer's stewardship in October 1983.

Another somewhat bizarre and short-lived publication of that era which didn't survive into 1983 was Noise! (it's that exclamation mark again!), which eventually merged with the Record Mirror, having failed to find an audience for it's claimed holy trinity of "Pop, Punk and Metal", the middle genre sadly once more largely restricted to the skinhead and mohican bands of that era on the pages within, although some of the newer bands did feature, as can be seen from this great Kirk Brandon cover from the spring of 1982 (a couple of months after the infamous wobbly mic TOTP performance had briefly made them the talk of the nation's living rooms). Needless to say, The Sisters did not feature within Noise!'s glossy pages...

|

Whilst TSOM were featured in the Washington Post and other well-respected national media in the US throughout their 1983 to 1985 tours, and Temple of Love would garner a half-page review (see below) in Belgian’s high circulation comic strip magazine Tintin Weekly (Kuifje Weekblad), the Sisters were largely ignored by even the specialist music media in the UK even after signing to Warners in 1984, with their only UK TV appearance coming after Gary Marx had ultimately left the band and the first coverage by mainstream national papers tragically only beginning with the Royal Albert Hall gig, the original band’s last rites).

Andrew Eldritch’s own intransigence and frustrations when it came to the London-based music industry were clearly contributing factors when it came to the lack of wider exposure which the band should have been able to command in 1982 and 1983, but the music media industry itself, and its inability to spot what was happening around the country, as seen through the prism of the short-lived Punk Lives!, was clearly the major issue.

My thanks for this post are due (once again) to TSOM fan and archivist Ade M for the Tintin cutting, to Tony P for the My Archive FB collection of magazines of the era and to the curators of the excellent Punk Lives! archive, which is well worth a browse. Those with a keen interest in the early years of The Sisters of Mercy are most welcome to join the unofficial Facebook group covering that era.

.jpg)